Sound Waves

Sound is a type of wave motion that propagates through an elastic medium from a vibrating source to a listener. It is classified as a longitudinal wave.

Sources of sound include animals, moving aircraft, vehicles, and vibrating tuning forks.

Sound is also a mechanical wave, meaning it cannot travel through a vacuum. A medium is necessary for its propagation. This explains why astronauts on the moon communicate using walkie-talkies, as there are no air molecules to transmit sound.

Transmission of Sound

Sound waves originate from vibrating systems and propagate as compressions and rarefactions. Since sound requires a material medium, it cannot travel through a vacuum.

The speed of sound depends on the density, elasticity, and temperature of the medium. Examples include:

- Speed in air at \(0^{\circ}C\): 330 m/s

- Speed in water: 1500 m/s

- Speed in steel: 5000 m/s

Wind also influences sound speed. If the wind moves in the same direction as the sound, it increases the perceived loudness; if opposite, the sound weakens. Additionally, in air, the speed of sound increases by approximately 0.6 m/s per degree rise in temperature.

The velocity \( v \) of sound is related to Young’s modulus \( E \) and density \( d \) as follows:

\[ v \propto \sqrt{\frac{E}{d}} \]

In gases, the velocity is independent of pressure but proportional to the absolute temperature \( T \):

\[ v \propto \sqrt{T} \]

Applications of Sound Waves

- Echoes: Sound reflected from a surface can be used to determine the speed of sound in air.

- Sonar: Ships use sonar to measure sea depth by timing sound wave reflections.

- Geophysical Exploration: Sound waves help detect underground minerals by analyzing reflections.

- Reverberation: Multiple reflections of sound in a hall can be controlled with padding.

- Beats: When two similar frequencies interfere, a periodic rise and fall in sound intensity occurs.

- Doppler Effect: A change in pitch occurs when there is relative motion between a sound source and an observer.

Characteristics of Sound

A musical note differs from noise based on specific characteristics:

- Pitch: Determines how high or low a note sounds, depending on frequency.

- Quality: Differentiates instruments playing the same pitch and loudness.

- Loudness: Depends on sound intensity and perception.

| Characteristic | Factor Affecting It |

|---|---|

| Pitch | Frequency |

| Loudness | Amplitude |

| Quality | Harmonics |

Resonance and Forced Vibration

Resonance: Occurs when a vibrating body induces vibration in another object at its natural frequency.

Forced Vibration: A body is made to vibrate due to continuous external influence rather than its own natural frequency.

Vibrations in Pipes

Closed Pipes: A pipe closed at one end produces only odd harmonics.

Fundamental frequency:

\[ f_0 = \frac{v}{4l} \]

First overtone (third harmonic):

\[ f_1 = 3f_0 \]

Credit: Topperlearning

Credit: Topperlearning

Open Pipes: Both ends are antinodes, allowing all harmonics.

Fundamental frequency:

\[ f_0 = \frac{v}{2l} \]

First overtone (second harmonic):

\[ f_1 = 2f_0 \]

Higher harmonics follow the sequence \( 3f_0, 4f_0, 5f_0, \) etc.

Example

Problem: The frequency of a fundamental note from a closed pipe is 250 Hz. What is the frequency of the next possible note from the same pipe?

Solution:

For a closed pipe, the possible harmonics follow the pattern:

\[ f_0, \quad 3f_0, \quad 5f_0, \quad \dots \]

Given that the fundamental frequency (\( f_0 \)) is 250 Hz:

\[ f_0 = 250 \text{ Hz} \]

The frequency of the next harmonic is:

\[ 3f_0 = 3 \times 250 \text{ Hz} = 750 \text{ Hz} \]

Answer: The frequency of the next harmonic is 600 Hz.

Velocity of Sound Wave in Air (Resonance Tube)

The velocity of sound in air using a resonance tube is given by:

\[ v = 2f(l_2 - l_1) \] where:

- \( v \) = velocity of sound in air

- \( f \) = frequency of the vibrating air column

- \( l_1 \) = first resonant length

- \( l_2 \) = second resonant length

Overtones in Strings

Musical instruments such as guitars and violins produce sound when a string attached to a sound box vibrates. The frequency of the sound produced depends on the following factors:

1. Length of the String

The frequency is inversely proportional to the length of the string:

\[ f \propto \frac{1}{l} \]

Comparing two strings:

\[ \frac{f_1}{f_2} = \frac{l_2}{l_1} \]

2. Tension in the String

The frequency is directly proportional to the square root of the tension:

\[ f \propto \sqrt{T} \]

Comparing two cases:

\[ \frac{f_1}{f_2} = \sqrt{\frac{T_1}{T_2}} \]

3. Linear Density of the String

The frequency is inversely proportional to the square root of the linear density (\( \mu \)):

\[ f \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu}} \]

Comparing two strings:

\[ \frac{f_1}{f_2} = \sqrt{\frac{\mu_2}{\mu_1}} \]

4. Linear Density Definition

The linear density of a string is defined as the ratio of its mass to its length:

\[ \mu = \frac{m}{l} \]

5. Velocity of Sound Wave in a String

The velocity of a sound wave in a string is given by:

\[ v = \sqrt{\frac{T}{\mu}} \]

where:

- \( T \) = tension in the string

- \( \mu \) = linear density of the string

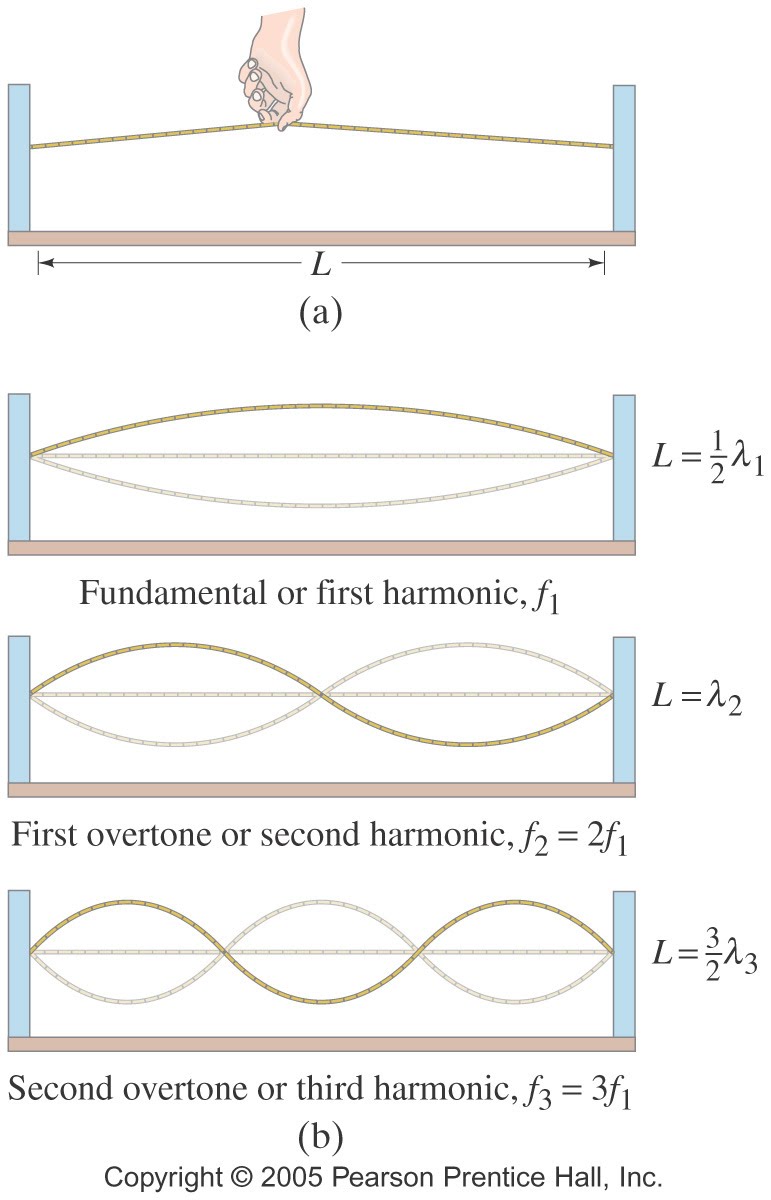

Fundamental Frequency

When a string vibrates in its fundamental mode, the distance between successive nodes is:

\[ l = \frac{\lambda}{2} \]

which implies:

\[ \lambda = 2l \]

Frequency of the fundamental mode:

\[ f = \frac{v}{\lambda} \]

Since \( v = \sqrt{\frac{T}{\mu}} \), we get:

\[ f_0 = \frac{1}{2l} \sqrt{\frac{T}{\mu}} \]

Credit: Kaiserscience

Credit: Kaiserscience

First Overtone (2nd Harmonic)

For the first overtone, the frequency follows a similar pattern.

\[ f_1 = \frac{1}{l} \sqrt{\frac{T}{\mu}} \]

For the second overtone (3rd harmonics)

\[ f_2 = \frac{3}{2l} \sqrt{\frac{T}{\mu}} \]

For the nth overtone

$$ f_n=(n+1)𝒇_𝟎 $$

Musical Instruments

String Instruments (Chordophones)

String instruments, also known as chordophones, produce sound using stretched strings or chords. Their operation follows the equation:

\[ f = \frac{1}{2l} \sqrt{\frac{T}{m}} \]

This means that the frequency of the sound is:

- Inversely proportional to the string's length (\( l \))

- Directly proportional to the square root of the tension (\( T \)) applied to the string

- Inversely proportional to the square root of the string's mass per unit length (\( m \))

For example, a thick and loosely stretched guitar string will produce a low-frequency note, while a thin, short, and tightly stretched string will produce a high-frequency note.

These instruments generate sound through string vibrations. The strings can vibrate as a whole, producing the fundamental frequency, or in segments, creating overtones and harmonics. The quality of the sound depends on the combination of these frequencies.

Common examples of string instruments include the guitar, piano, violin, and harp.

Wind Instruments

Wind instruments, also known as aerophones, produce sound when air is blown into them. The sound is generated as the air column inside the instrument vibrates. The quality of the sound depends on whether the instrument is a closed or open pipe.

The frequency \( f \) of the note produced is mainly determined by the length \( l \) of the vibrating air column and follows the relation:

\[ f \propto \frac{1}{l} \]

This means that a shorter air column produces a higher-pitched sound, while a longer air column produces a lower-pitched sound.

Examples of wind instruments include the flute, clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, and mouth organ.

Percussion Instruments

Percussion instruments produce sound when struck, scraped, or hit. Their vibrations generate sound waves, and different materials and sizes affect the pitch and tone.

Examples of percussion instruments include the xylophone, talking drum, tambourine, and bell.

Beats

When two notes of slightly different frequencies are played together, the resulting sound experiences periodic variations in loudness. These fluctuations are known as beats.

Beats occur due to the interference of sound waves produced by the two notes. The beat frequency \( f \) is the number of beats heard per second and is given by:

\[ f = \frac{1}{T} \]

Uses of Beats

- Used to determine the frequency of a tuning fork or measure an unknown frequency.

- Helpful in tuning musical instruments such as the piano.

Doppler Effect

The Doppler effect is the change in the observed frequency of a wave due to the motion of the source or the observer. This effect can be experienced when a moving police siren approaches or recedes from a stationary observer.

As the siren approaches, the sound increases in pitch, and as it moves away, the pitch decreases.

The Austrian physicist and mathematician Christian Johann Doppler (1803–1853) first studied this effect in detail.

The observed frequency \( f_{\text{obs}} \) for a stationary observer and a moving source is given by:

\[ f_{\text{obs}} = f_s \left(\frac{c}{c \pm v} \right) \]

where:

- \( f_s \) = frequency of the source

- \( c \) = speed of the wave

- \( v \) = speed of the moving source

Note: Use the minus sign when the source moves toward the observer and the plus sign when it moves away.

For a stationary source and a moving observer, the observed frequency is:

\[ f_{\text{obs}} = f_s \left(\frac{c \pm v}{c} \right) \]

Note: Use the plus sign when the observer moves toward the source and the minus sign when moving away.

Applications of the Doppler Effect

- Used in ultrasound imaging to determine blood flow velocity.

- Helps measure the recession of galaxies, providing insights into the origin of the universe.